Hydrogen – the invisible elephant in the room?

Electric vehicle charging finally seems to be investable – but is hydrogen lurking in the background to jeopardise the investment case?

New investment opportunities

For years, the electrification of transport has appeared inevitable. We have experienced a strong shift towards electric vehicles, especially in 2020. When car dealerships in Europe opened up after the initial lockdown period, electric vehicle sales picked up right where they left off, and in some markets surpassed sales for diesel vehicles.

While this revolution is well on its way, investment in EV charging has remained more difficult. Profitability in the sector is linked to utilisation. And with EV penetration still in single-digit percentages, utilisation remains uncertain. This makes on-road charging more of a longer-term proposition. More recently, however, business models have been established that could change this. Certain fleet vehicles – buses, delivery, long-distance logistics – have very predictable (scheduled) driving patterns. This also makes their charging needs very predictable.

In these segments, revenue streams are easier to project. If a fleet – commercial or public – is electrified, these vehicles will need charging, and a certain level of utilisation is guaranteed. The uncertainty can be even lower, if there is a contract in place between the fleet owner/operator and the charging provider.

What are we missing?

It seems that with these adjustments, investors can finally reap the benefits from the electric transport revolution. But is something unaccounted for about to jeopardise this opportunity?

Electric mobility is not the only energy trend that made headlines this year. It also seems that hydrogen is back, and finally ready to claim its place as an energy carrier. Dozens of projects have been announced in 2020, and many authorities, including the European Commission and the governments of Europe’s biggest countries have published their hydrogen strategies. In all of these strategies, hydrogen has a place in transport.

So will the rise of hydrogen mean fuel cell vehicles are about to displace battery electric vehicles in the bus, van and truck segment? Is an investment in bus, van and truck charging more risky than it seems?

Closing the gap?

In order to answer that question, let us consider two factors: user-friendliness and cost.

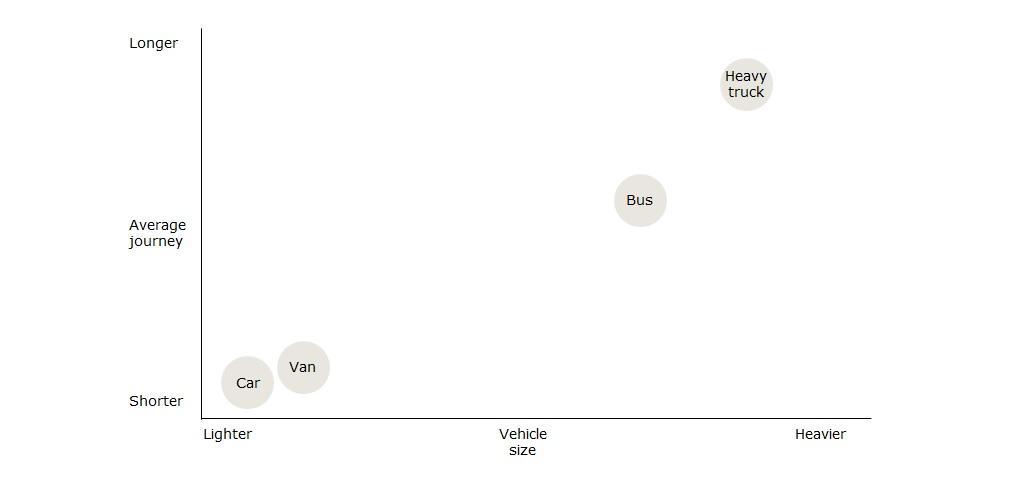

Heavy vehicles tend to drive longer mileages. When electrified, they either need very large batteries, or charge very often. It could be more practical to use hydrogen in these instances, as the refuelling would be more similar to a conventional diesel vehicle.

On the other hand, batteries have been developing rapidly. Electric trucks and buses are being deployed in many places. More deployment means more cost savings. If we are to believe that fuel cell vehicles can displace these battery vehicles, they would need to close a cost gap.

At present, electric buses enjoy a bit of a moment. National and local governments in countries such as the Netherlands, UK and Germany have implemented legislation to replace polluting vehicles. As a result, across Europe, more than 4,000 electric buses have been deployed. Compare this with only several hundreds of fuel cell buses expected to be operating at the end of 2020.

The question is this: How much of this is due to expected costs and how much to a mere lack of choice and availability when it comes to hydrogen vehicles?

Competing on cost?

What would need to happen for fuel cell vehicles to compete with battery vehicles on both cost and convenience terms?

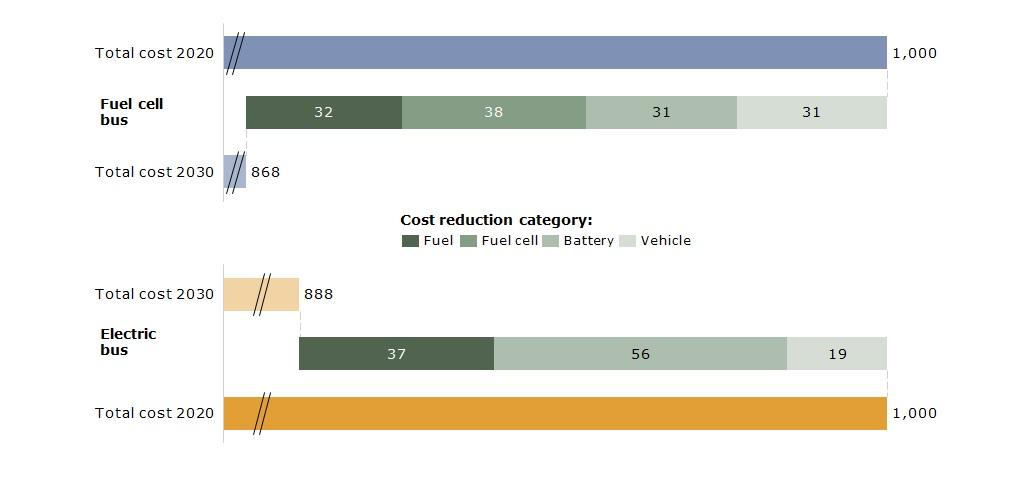

As far as costs are concerned, the two vehicle types might actually be very close. Both a battery electric bus and a fuel cell bus would cost close to €650,000. For the battery variant, the battery accounts for around 15% of the capex. In a fuel cell bus, the fuel cell plus battery accounts for around 17%. Assuming electricity comes at around €0.15/kWh and hydrogen for around €10/kg, both options, over a 20-year lifetime, would come close to €1mn in total cost of ownership.

In 2030, if we expect hydrogen to play a larger role in the economy, and therefore costs to drop by 50% to €5/kg, the hydrogen vehicle could be cheaper. Additionally, fuel cells could fall more in cost than batteries, making the difference even larger.

Carried away?

So it appears that the from a pure cost perspective, fuel cell vehicles could be very attractive in segments such as buses and trucks. However, the cost element is just one of many issues to be solved along the way.

There is currently a real lack of hydrogen vehicles on the market. This means there is a lack of competition and also a lack of understanding and knowledge in the supply chain.

Secondly, hydrogen vehicles currently also suffer from a lack of infrastructure. When electric vehicle drivers sometimes struggle to find the right charging solutions at times when they need it, this is even more problematic for hydrogen vehicle drivers – considering there are close to 200,000 EV charging points in Europe, compared to about 200 for hydrogen.

Finally, the above highlights the importance or reducing fuel costs. With a better infrastructure, there is no question hydrogen costs to the consumer could come down from the current €10/kg. However one must also remember that one of the key points to switching from diesel to an alternative is reducing the carbon impact. If the hydrogen is not produced in a clean manner, the resulting impact on emissions overall might not go far enough. And producing hydrogen in a sustainable way is, and will for some time be, more expensive than the conventional way.