Risk aversion

Building resilience in the new, riskier gas market

Nord Stream 1 exists because of Russia's difficult relationship with an independent Ukraine. Russia was reliant on Ukraine to transit its gas to Europe; and between 2006 and 2009 Gazprom and Ukrtransgaz were in dispute over transit fees. The political desire to bypass the problem of being beholden to Ukraine, led Russia to build two expensive subsea pipes directly to Germany. By itself these two subsea pipes (Nord Stream 1) could only divert about half of the gas flowing via Ukraine, so for total independence in its gas export capability, Russia planned and built a second Nord Stream.

Investors in Nord Stream 2 had to abandon the project following sanctions from the US, which foresaw an

over-reliance on Russian gas; and the project was finally completed by Gazprom alone.

Before invading Ukraine, the Kremlin exerted as much pressure as contractually possible - through creating

'artificial scarcity' and pushing up prices - to encourage Germany and the EU to commission Nord Stream 2. On this occasion though, they did not oblige, and Russia has been left without the export flexibility it desired.

This has not stopped gas providing arguably the most effective lever the Kremlin can pull to exert political pressure on Europe. Very few commentators would disagree that the Kremlin has abandoned contractual obligations, and Gazprom's standing as a reliable supplier, in favour of furthering its wartime objectives, completely changing the risk landscape for European energy.

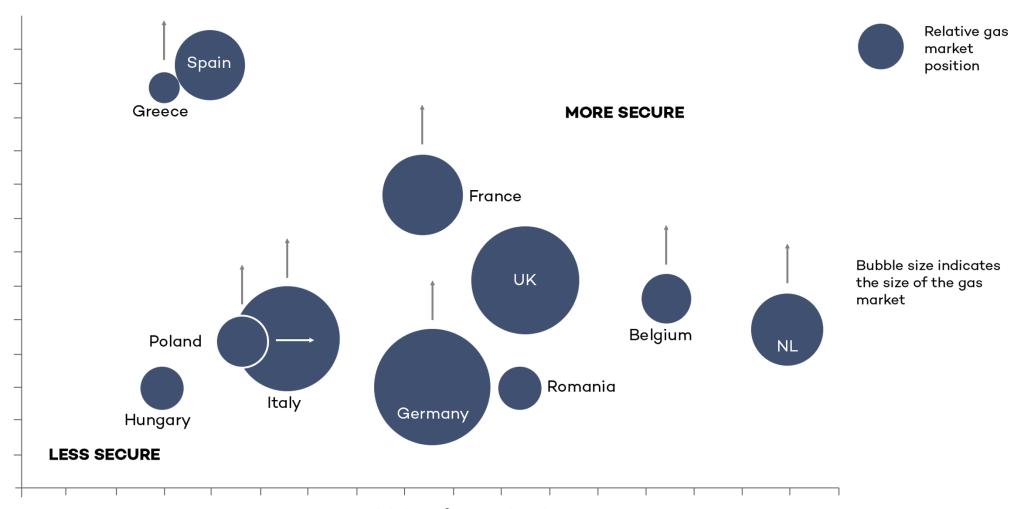

So Europe is looking to build its way back to energy security, and in the gas market this means more LNG re-gasification capacity and maximising local reliable gas supplies, mainly from Norway. The bubble chart shows the relative security of supply position of a sample of European countries; illustrating the importance of indigenous production, pipelines from the North Sea and access to the global LNG market. Italy and Spain have access to pipeline supplies from North Africa, which arguably makes them more secure than illustrated here, although these routes have been subject to disputes and interruptions in recent times.

Availability of secure local gas = 2020 supply of EU +UK +Norway gas and indigenous production (as% of 2021 gas demand)

Sources: BP Energy Statistics 2021 and 2022, and AFRY Central scenario

The positions of Slovakia and Czechia are identical to Hungary, as would be Poland's if it had not been an early mover to diversify away from Russian gas; and, Poland also has the contracts in place to secure itself with US and Qatar for LNG, and for Norwegian gas via the new Baltic Pipe. Hungary has also taken a different political stance to the rest of the EU and stands out as a lone EU member state that has done a deal this August to contract further gas supplies from Gazprom.

The EU would like to see all its states reduce their overall gas demand which is an effective method for reducing the risks from a volatile gas market. However, finding alternative fuels to gas can be very challenging and the transition will take time; so in the meantime companies, governments and regulators are trying to better understand the risks from the global gas market and how best to mitigate against them.

Security of supply analysis normally relies on two factors: the magnitude of a risk and the probability of it occurring. Historically the risk of total interruption of Russian gas was quantified as having a huge magnitude but this was always combined with an extremely low probability. The risk of an interruption to gas transiting Ukraine was considered quite likely, but this was considered greatly mitigated once Nord Stream 1 existed.

These assumptions are clearly no longer any good – Nord Stream 1 has been sabotaged and is unlikely to ever restart, allowing Gazprom to call force majeure on many of its contracts.

In future, stakeholders in the gas market need to assess their risks by keeping a keen eye on where the next threat to gas supplies is likely to arise. The global gas market is connected by LNG, which travels by ship, and this means governments trying to protect their gas supplies need to monitor world events – including, weather and warfare.

A long history of reliability is not a reason to discount risks along the supply chain from a particular supplier. Some examples of risks from the LNG market are as follows:

- Qatar has been a reliable LNG supplier, with enormous LNG production capacity, but on route for Europe its ships must pass through the Straits of Hormuz (between Iran and UAE) and the Suez canal – both of which have been liable to political and physical constraints.

- Less significant to Europe is the Panama canal, which acts as a bottle neck to LNG produced on the East Coast of the US travelling into the Pacific. This route has also been the cause of market disturbances.

- The shipping market itself and the charter rates for LNG carriers and FSRUs (floating storage and regasification units – now so desirable in Europe) are highly volatile.

- It is not unusual for the charter rates to quadruple within a month or two, and not fall back for several months. The northern hemisphere winter is an exceptionally expensive period this year, in a particularly tight market resulting from the removal of so much Russian gas.

- Another threat could come from LNG demand in other parts of the world – such as Japan and China. The Fukushima disaster in Japan is an example of an unexpected accident leading to high demand for LNG and high prices. China has a huge energy demand and it is hard to predict its preferred source for that energy. Given the sheer scale of China’s energy demand and its use of gas in residential heating means the weather in China can have significant impact on global LNG demand.

In future, security of supply analysis should assess mitigations for even seemingly unlikely occurrences and take much closer notice of developing geopolitical situations. Locally sourced energy will be the foundation of secure systems with a diverse range of international sources to spread geopolitical risk. To paraphrase Winston Churchill when he was First Lord of the Admiralty and he was considering the security of oil supplies, “safety and certainty in gas lie in variety and variety alone”.