Round and round – the European bus sector in motion

Awareness about climate change and air quality has increased recently. This, alongside new national and EU-wide policy aiming to reduce emissions from cars, buses and trucks means that the next decade will bring a major shift from diesel and gasoline vehicles to cleaner alternatives. In this series of articles, we explore what that shift means for the energy sector, networks, fleet management, financing, recycling, among others.

More than 700,000 buses are in operation today in the EU. The three biggest operators – Poland, Italy and France – account for almost half of that number, with Germany and Spain also home to large bus populations. The vast majority of these vehicles – 19 out of every 20 – runs on diesel.

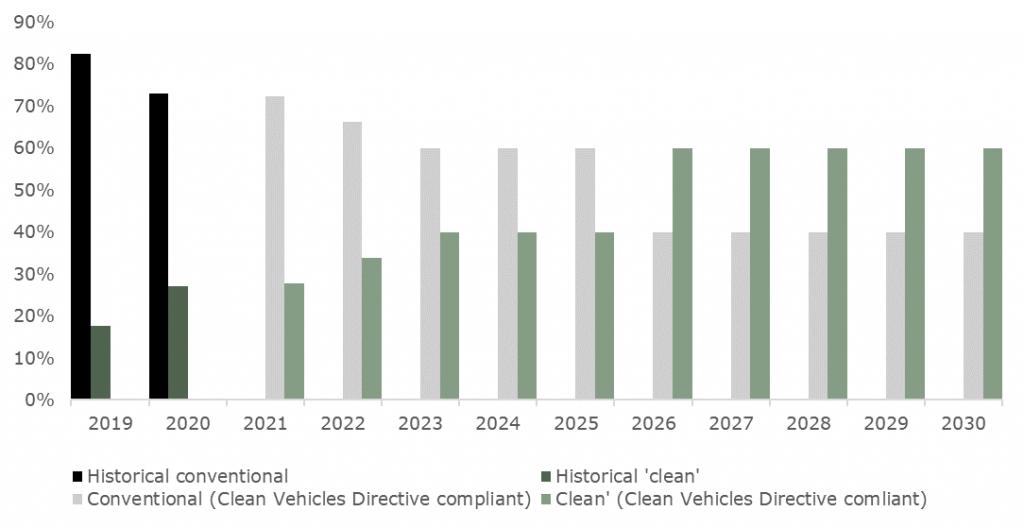

By 2030, almost 2 out of every 3 new buses across Europe will need to be ‘clean vehicles’ as defined by the Clean Vehicle Directive, depending on the EU member state. The Directive still needs to be implemented in national law, however it already appears that several countries and cities may in fact opt for something even more stringent. For some municipal transport companies in these countries it means they have already stopped or soon stop purchasing any fossil fuelled vehicles.

A bus is a significant investment. For a typical diesel city bus, capex can be between €250k and €350k. Alternatives, such as electric, hydrogen, or natural gas vehicles, are significantly more expensive to purchase. They also come with extra costs for infrastructure and, depending on the option, batteries.

Of course, dealing with an electric bus fleet is fundamentally different than dealing with a diesel bus fleet – on many levels. The supply of energy is very different. Today's bus depots generally house a few fuelling points and storage tanks for diesel only, with the fuel itself being delivered by fuelling trucks, stored for long periods and used when needed. For an electric fleet, the depot needs to have a strong power network connection and numerous electric charging points in order to allow for slow overnight charging of the fleet and there needs to be a set of very high-power chargers in several other locations to allow for opportunity charging.

Operators need to think about the fleet not just in terms of vehicles, but vehicles, batteries and the charging infrastructure. Charging times and locations need to be reflected in bus schedules, and batteries may have to be replaced several times over the lifetime of the bus chassis. The combination of vehicle and battery also makes it more complex to finance bus fleets. Typically, the residual value of a bus after its use is very low, so there is little risk and little upside in, for example, a lease arrangement. However, the uncertainty around batteries (e.g. state of health over time, ability to re-use or re-purpose for a second life, recycling value) does complicate matters.

We expect a large share of the future bus fleet to be fully electric. In 2020, 6.1% of new bus sales in Europe were battery electric vehicles, with an increase of 18.4% over 2019. This trend is set to continue, even though natural gas and even fuel cell buses could also play an important role. The chart below shows how the market share of ‘clean’ vs. conventional buses could develop under the Clean Vehicles Directive measures. With 30,000-40,000 buses registered every year in Europe, a 40% market share for clean buses (largely in line with the Clean Vehicles Directive targets until 2025, which also includes other options such as hybrids or fuel cell vehicles) would mean up to 16,000 low emission buses per year. From 2030 onwards, this could increase to over 25,000.

All of these alternatives come with their own unique challenges, which makes deciding between them very complex. We will explore that decision in a future article. Next week, we will take a closer look at the Clean Vehicles Directive, and whether it can ensure for the immediate future and beyond that the determination towards a more sustainable bus sector continues and accelerates.