"Get Brexit Done" - the Impact of Brexit on EU ETS Carbon Prices

Carbon price movements under the EU ETS have been intimately linked to Brexit developments of late. In theory these movements should diminish now the Conservative government finally has enough political capital to pull the UK out of the EU. But how and when will the UK leave the EU ETS? Is a no-deal scenario really off the table? And how does the impact of Brexit on the EU ETS compare to other material risks like tighter decarbonisation targets or coal phase-out?

How and when might the UK leave the EU ETS?

With Boris Johnson’s majority government in place the UK is now likely to exit the EU by 31 January 2020 via a transitional departure period that runs until the end of 2020. UK installations would remain in the EU ETS until that date, which is also the end of Phase 3 of the EU ETS (2013-2020). The UK is aiming to instigate its own UK-only ETS to start in January 2021, which will then be linked to the EU ETS as soon as possible. In terms of fundamental supply and demand, a linked UK-EU ETS is the same as if the UK were to stay in the EU ETS (our base case assumption), but there may be some hiccups along the way as discussed below.

EUA prices in 2020 could slump as the UK issues two years’ worth of allowances in just 12 months

Current arrangements have barred the British government from allocating or auctioning any 2019 EUAs until a withdrawal agreement has been ratified by both parties. Now the UK is expected to be allowed to commence free allocation and auctions for 2019 early in the new year, potentially trying to compress a year’s worth of allowances (~125m EUAs) into just three or four months, ahead of the compliance deadline for 2019 of 30 April 2020. This influx of allowances into the market, on top of the issuance of UK allowances for 2020, is likely to have a bearish impact on the market in the short-term. Meanwhile UK installations without European counterparts may offload any stockpiled EUAs that are surplus to requirements beyond the end of 2020, which would compound this bearish movement (~€4-5/tCO2 for the next 5 or so years).

Is a no-deal scenario really off the table?

The Withdrawal Agreement is expected to pass smoothly through UK parliament and be ratified by the European Parliament by 31 January 2020. Then attention will turn to the transition phase, which locks UK trading arrangements with the EU on its existing terms until the end of December 2020. During this period the Johnson government will negotiate the future post-Brexit relationship with the EU – everything from trade to defence to science. If a trade deal fails to be agreed, the UK is set to leave the EU without a deal and would trade with the EU on World Trade Organization terms. With relationships frayed, the UK is unlikely to be in a position to link its new UK-only ETS with the EU ETS. Below we discuss the impact of this ‘no-deal no-linked’ scenario.

Could a no-deal no-linked UK exit from the EU ETS be bullish and lead to higher carbon prices?

We have probed the impact of a UK exit using AFRY’s carbon model, Aether, which uses a linear optimisation to minimise the cost of delivering the required abatement to meet decarbonisation targets. Combined with our detailed power market modelling, Aether models the cost of meeting the EU ETS cap in the power sector, in the industrial sectors, and incorporates both the behaviour of the MSR and the behaviour of market participants.

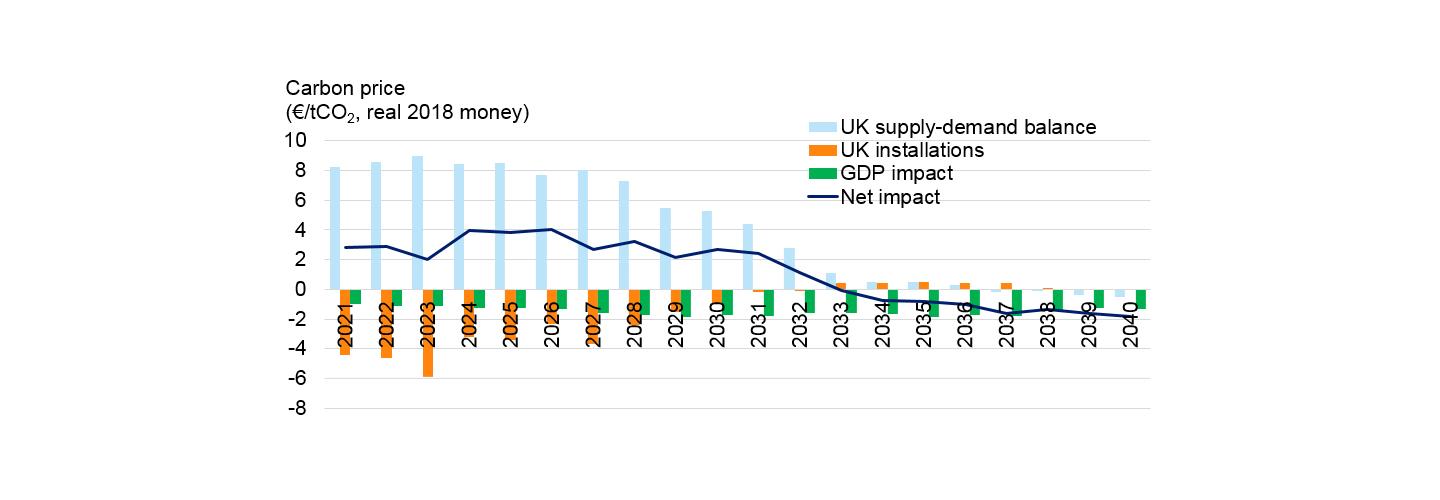

Below we show the modelled impact of a permanent UK exit from the EU ETS as of 1 January 2021, relative to a base case whereby the UK links with the EU ETS. Contrary to recent market reactions linked to Brexit news, our fundamentals analysis shows that a non-linked UK exit from the EU is likely to be bullish, raising prices €2-4/tCO2 throughout the 2020s.

In the event of a ‘no-deal no-linked’ Brexit, the impact on the carbon price is governed by three interacting drivers

-

Removing the UK net exports of allowances

-

UK installations offloading surplus allowances

-

GDP impact of a no-deal Brexit reduces industrial output

Note the first two factors are relevant in any no-linked scenario, whereas the GDP impact is specific to a no-deal scenario.

These three fundamental drivers are discussed below:

1. The UK leaving the EU ETS removes a net exporter and creates a tighter market

-

The UK has historically been a net importer of allowances e.g. from 2013 to 2015 UK emissions exceeded the UK supply of EUAs by 15%. However, aided in part by a rapid phase-out of coal generation, from 2016 onwards the UK has been a net exporter of allowances with supply exceeding emissions by ~12% in 2017 and 2018, and is expected to continue doing so into the 2020s. The remainder of the ETS would be tighter once the UK exits, causing an ~€8/tCO2 price increase for most of the next decade.

-

Our analysis suggests this situation reverses beyond the mid-2030s, since by that time aviation has become a significant share of emissions, of which the UK has a disproportionate share.

2. UK installations offload surplus allowances could reduce the carbon price

-

Without clarity on a future link, UK entities without partner EU installations are likely to choose to offload surplus allowances, rather than gamble on whether these stockpiled EUAs will be fungible with a UK-only ETS.

-

Surplus volumes held by UK installations could be on the order of ~85m EUAs, equivalent to 60% of UK 2019 emissions. Of this, we estimate approximately 50% is being held by UK installations without operations in mainland Europe. Releasing this on the market would reduce the carbon price by €4-5/tCO2 for the next 5 or so years.

3. GDP impact of Brexit reduces industrial output

-

EUA prices are sensitive to GDP and industrial output. Reduced output makes it easier to meet emission reduction targets resulting in lower carbon prices, as illustrated by the 2008-09 financial crisis.

-

Opinions vary on how much mainland European GDP will decline in the case of a no-deal Brexit. In our analysis, we have assumed 0.6% loss in emissions across the EU ETS sectors (power, industry, aviation, and district heating), and this, in turn, causes prices to decrease €1-2/tCO2 over the modelled period.

The overall price impact of a UK exit from the EU ETS is governed by the interaction between the fundamental drivers:

-

a looser market is created by the actions of UK installations offloading unwanted EUAs and reduced GDP growth; whilst

-

a tighter market is created by the impact of UK’s supply-demand balance (at least over the next decade).

Most of the commentary around Brexit relates to the two bearish drivers which create a looser market, without acknowledging the impact of the UK’s supply-demand balance, which could account for the perception that a no-deal no-linked Brexit will be bearish.

Is the impact of the UK leaving the EU ETS particularly significant compared to other risks?

With carbon market commentary having been so transfixed on Brexit it is easy to forget other factors that could cause carbon prices to crash. Such risks include:

-

EU ETS decarbonisation targets are not tightened;

-

market participants dumping stockpiled allowances; and/or

-

coal phase-out occurs without cancellation of EUAs.

Is the market currently assuming decarbonisation targets will be tightened?

Momentum is undoubtedly building to tighten future EU ETS cap levels – on 11 December EU leaders announced an agreement to target net-zero emissions by 2050 had been agreed but acknowledged that Poland was unable to commit to the goal at this point.

Meanwhile, the new President of the EU, Ursula von der Leyen, is calling for a -50-55% economy-wide 2030 target (relative to 1990) with an impact assessment scheduled to be published by “summer 2020”, followed by legislative proposals made by June 2021. This may translate into a -52-62% EU ETS 2030 target (relative to 2005), significantly tighter than the current 2030 target of -42% (relative to 2005).

The market may already be assuming targets are tightened imminently as there is currently a large disjoint between traded EUA prices and what we project assuming fundamental economics (i.e. modelling the underlying supply of EUAs and cost of abatement). Our own analysis based on fundamentals suggest prices should be 5-10/tCO2 lower than current market prices assuming currently legislated decarbonisation targets.

Could stockpiling of allowances be inflating market prices?

The current market is characterised by its historical oversupply of 1.7 billion EUAs, equating to approximately a year’s worth of emissions. For the market to clear at current prices one would have to believe that ~75% of the current oversupply (1.3bn of 1.7bn EUAs) are being held independent of price, perhaps through a combination of:

-

conservative industrial players, who have an existential strategic imperative to stockpile EUAs so as to ensure European production can be maintained over future years as emission caps tighten; and/or

-

state-owned entities who may be obligated by their parent states to effectively withdraw allowances from the market; and/or

-

market-making purposes by financial institutions and other trading parties keen to develop a stable market in carbon.

If this explanation was correct and a third of current stockpiles were released, carbon prices would crash by approximately €9/tCO2.

Could coal phase-out without adjusting the EU ETS collapse carbon prices?

Recent announcements in France, Ireland, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and Germany indicate a move towards earlier than originally anticipated closure of coal power plants. This will most likely depress EUA prices in the absence of a tightening of EU ETS targets or the voluntary cancellation of allowances.

Germany, which currently accounts for around one third of the EU’s coal capacity, is aiming to phase out coal by 2038. On 9 December Germany re-affirmed it would proceed with EUA cancellations to offset the market impact of its coal phaseout. But until a robust methodology for cancellation is passed into law (forgoing billions of Euros in auction revenue in the process) the risk is this will not occur. Meanwhile, in Poland, there are no firm Government-led plans for decommissioning coal/lignite capacity, but new capacity is excluded from the Polish capacity market from July 2025 onwards.

Assuming significant coal capacity closure takes place without any voluntary cancellation of allowances in Germany and Poland, we could expect carbon prices over the period from 2020 to 2040 to be up to €15/tCO2 lower than if allowances were cancelled (or the plants were not decommissioned). Inclusion of further coal phase-out without EUA cancellation in other markets would see this figure rise.

Lots of big risks, but a ‘no-deal no-linked’ Brexit doesn’t make the top three

We believe there are several reasons for why the carbon prices under the EU ETS may crash, but the UK leaving the EU ETS is not one of them – on the contrary, it could be in fact be bullish. The magnitude of the changes from tightening caps, dumping of stockpiled allowances by industrials or from accelerated coal phase-out by governments dwarfs the Brexit risks. As a result, market participants should be looking to the government policy towards coal plant and announcements from the new EU president to understand what the future may hold.

If you are interested in discussing some of the issues raised here or have other questions related to the EU ETS please get in touch with Mostyn Brown.