Dual benefit

Russia’s weaponisation of food threatens to bring about global food shortages

International leaders, including Biden, Modi and Von der Leyen, have all condemned Russia’s weaponisation of food since its invasion of Ukraine, which has taken the form of restricted Ukrainian and Russian exports of fertiliser and agricultural products. In particular, Russia is the world’s largest exporter of nitrogen fertilisers, and its producers benefit from access to competitively priced gas, which is the key feedstock for most of the world’s production of ammonia, the raw material for nitrogen fertilisers. Russia’s suspension of gas supplies to Europe compounded the fertiliser shortage, leading to the closure of up to 70% of European ammonia capacity at its worst, and fertiliser prices reaching record highs in 2022. Such is nitrogen fertiliser’s importance to overall food security that the United Nations forecasts that 2022’s shortages of nitrogen fertiliser may result in a massive loss of 66 million tonnes of staple crops in 2023, enough to feed almost half the world’s population for a month.

Balancing food security and decarbonisation

Whilst nitrogen fertiliser plays a crucial role boosting worldwide crop yields, its synthetic production and use also accounts for around 2% of global emissions, meaning that finding the optimal balance between global food security and decarbonisation is difficult. It is consequently perhaps unsurprising that governments and companies are seizing upon the opportunity to develop green ammonia, utilising local renewable energy supply (RES) and electrolysis to produce domestically low-carbon fertilisers, as a means by which to address fertiliser availability and affordability, and food security, whilst also decarbonising. According to the International Energy Agency, production of conventional gas-based ammonia (“grey ammonia”) generates direct or scope 1 emissions of 2.4 tonnes CO2 /tonne of product, far in excess of commodities such as steel and cement with direct emissions of 1.4 t and 0.6 t CO2 /t respectively. The prospect of zero direct emissions with green ammonia production is therefore especially attractive to governments targeting meaningful emissions reductions.

Green ammonia not a one-size-fits all solution

Green ammonia production is most likely to be attractive as a means to improve food security to those countries currently either a) heavily reliant on imported nitrogen fertilisers, for example, Brazil, India, and the EU, the world’s largest importers, and/or; b) those countries where food scarcity is a major issue, for example, in sub-Saharan Africa where fertiliser application rates (and in turn imports) are low, resulting in sub-optimal crop yields.

Many of these countries also show some potential for competitively priced RES, suggesting in principle the suitability of domestic green ammonia production to improve national food supply, although in reality its appropriateness will vary by country. There are a number of challenges facing green ammonia projects aimed at alleviating food security, some of which are outlined below, including potential mitigating actions from government actors.

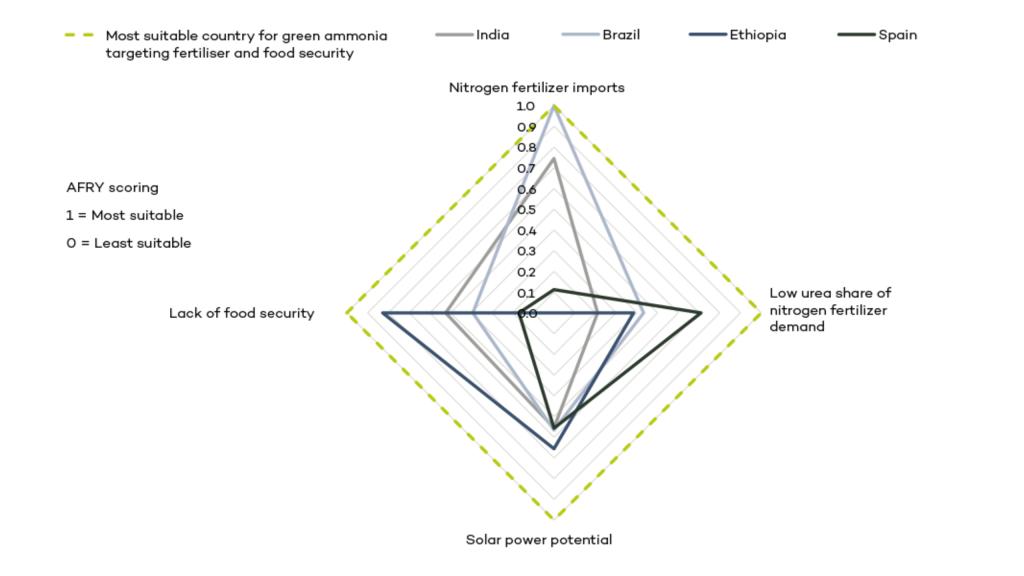

Green ammonia rarely one-size-fits all

Suitability ranking of selected countries for green ammonia production as a solution for food and fertiliser security

Fertiliser affordability and willingness to pay

Increasing domestic ammonia supply via green ammonia will not guarantee an improvement in domestic fertiliser affordability, in fact in the medium-term quite the opposite may occur. One of the most significant challenges facing green ammonia production presently is its high costs relative to grey ammonia. For example, AFRY estimates a Levelised Cost of Ammonia (LCOA) for a representative European green ammonia project of €1,000/tonne. Whilst this was below European ammonia price levels for much of 2022, it is well in excess of more typical prices, for example over 2012-2020 prices were more in the range of €250-550/tonne.

The exact costs of green ammonia projects will be location and project specific, but important cost drivers will be the cost and variability of RES, and how the project is optimised and sized with storage options to manage the RES variability versus the flat demand profile of an ammonia plant. Other key drivers will be capex, especially for the electrolyser, and financing costs.

There are a number of factors that could serve to bridge the gap between the LCOA and farmers’ Willingness to Pay (WTP), including penalties for grey ammonia production, most notably carbon pricing, development of a “green premium” reflecting the additional value perceived by consumers for the low emissions profile of green ammonia, or alternatively government support.

However, in lower income countries facing more severe issues with food security, there is limited carbon pricing to date, and the ability to pass through a green premium will be constrained by higher elasticity of fertiliser demand to price changes, owing to the larger share of fertiliser costs relative to farmer income. Moreover, fertiliser price increases can also impact food supply through demand destruction and the resulting reduction in crop yields.

As a result, whilst green ammonia costs reduce, government support will most likely be required to bridge the gap with grey ammonia. This could take the form of: a) increased subsidisation of farmers’ fertiliser purchases, or of project developers, most notably seen currently in the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which is providing aggressive production and investment incentives; or b) via contracts for difference, as currently seen in the H2 Global tender for ammonia where the German government is set to pay the difference between the supply and offtake tender prices. This platform is set to be used EU-wide for fixed premium auctions planned under the European Hydrogen Bank.

Fertiliser demand and the loss of CO2 production for urea

Green ammonia is often sold as bringing fertiliser self-sufficiency, ignoring the fact that only 3% of ammonia is directly applied as a fertiliser globally. In reality, most ammonia in fertiliser production is used as an input into urea, nitrate, and other fertilisers. Additional processing capacity will be required for full fertiliser import substitution. The shift to green ammonia production removes the CO2 generation that many grey ammonia producers use in the integrated production of urea, the world’s most heavily consumed nitrogen fertiliser, accounting for nearly half of the global market, with India and Brazil both major urea markets. Moving to green ammonia therefore alters the economics of integrated urea producers, leaving them seeking alternative CO2 sources. It is hoped that this issue can be overcome by a shift to nitrate fertilisers, given their production does not consume CO2 and their overall carbon footprint including scope 3 emissions is lower. Whilst this may be possible in some markets, it is worth remembering that ammonium nitrate use requires higher regulatory costs and compliance in order to avoid accidents such as the Beirut 2020 explosion or use by terrorists.

Fertiliser availability

Currently, fertiliser accounts for 85% of global ammonia demand. As ammonia’s value as an energy vector grows, the market could grow nearly x3-5 times by the middle of the century, depending on its uptake as a mobility fuel, most likely in maritime applications, as well as in power generation and storage, and as a carrier of hydrogen. This means green ammonia produced for fertiliser use will face increasing competition from other markets, as well as competing for RES. Over time these markets should delineate more with product differentiation and standards, and different WTPs and infrastructure, but especially in the interim, there could be increased competition for ammonia typically destined for fertiliser production, as opportunistic traders take advantage of arbitrage opportunities.

Governments will need to consider other options for low-carbon ammonia, including developing other production pathways, such as blue ammonia using carbon capture and storage (CCS) or waste-to-ammonia. Alternatively, in offering support to plug project funding gaps, governments may need to lock in green ammonia volumes for use solely in fertiliser production.

Overall, it is evident that whilst green ammonia offers much potential for increasing domestic fertiliser supply, and in turn food security in different geographies, it does not offer this immediately, and to what degree will depend on the features of each country’s market and governmental support.