Leveraging the Past to Secure Our Future

Written by José Gonzalez and Łucja Wanicka

The US has the opportunity to establish itself as a front runner in the new circular economy for textiles, considering it is the second largest market for textiles in the world, and currently, only about 15 per cent of collected textile waste in the country is being recycled. While taking advantage of this opportunity is no easy feat, the burden can be somewhat lessened by leveraging key lessons learned from how paper recycling has become mainstream in the last few decades.

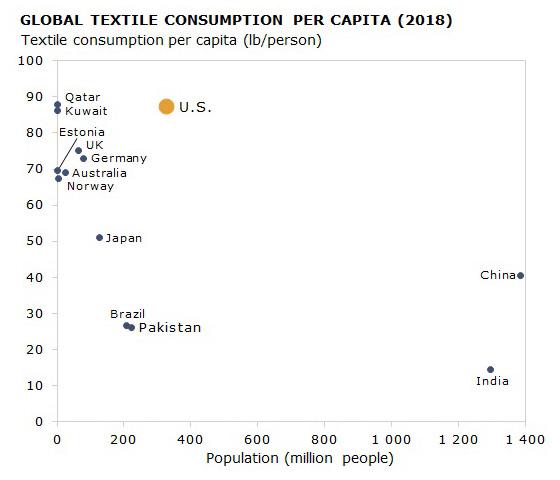

On a global scale, the consumption of textiles has more than doubled in the last 30 years, driven mainly by the growing world population, increasing share of middle-income citizens, and low-cost fast fashion becoming mainstream. Today, the US is the second largest consumer of textiles after China and accounts for roughly 15 per cent of the total market, which is approximately 120 million tonnes. Interestingly, the US also has the second highest textile consumption per capita (pounds of textiles consumed per person) of all countries in the world. Only Qatar, with a total population of slightly less than 3 million people, has a higher rate (see Figure 1).

This means that in addition to brands and retailers, consumers in the US are one of the key drivers of global textile markets and hold significant power and influence over the industry. And considering that clothing use (that is, the number of times a garment is worn before it is discarded) has been decreasing over the last two decades, it also means that the country has a lot of textile waste that needs to be appropriately dealt with.

Handling of Municipal Solid Waste in the US

According to the US EPA, the total municipal solid waste generated in 2018 was 292 million tonnes—almost a quarter of that was paper and paperboard, followed by food and other organics for compositing.

Interestingly, textile waste accounted for 6 per cent of total generated waste volumes, and according to Accelerating Circularity (a New York-based non-profit that catalyses new circular supply chains and business models to turn used textiles into mainstream raw materials), the US East Coast generates a significant portion the country’s textile waste, owing to its high population density and existing supply chains.

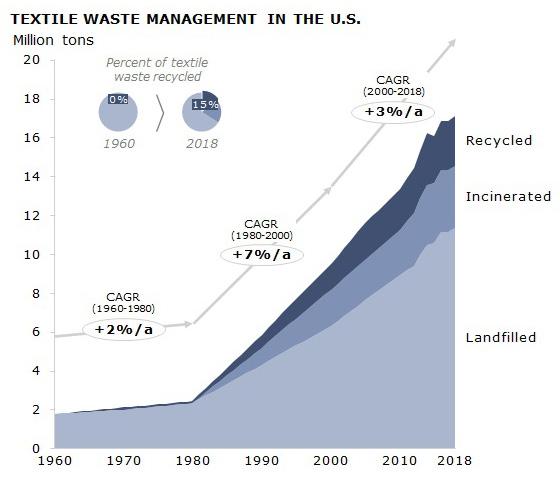

However, currently over two thirds of the textile waste generated in the country is being landfilled, some 15 per cent is incinerated, usually with energy recovery, while the remainder, also some 15 per cent, is recycled typically into lower value items such as wipers, shoddy, and insulation (see Figure 2). Estimates by Accelerating Circularity indicate that 35 per cent of the textile waste diverted to landfill and incineration is readily recyclable (composed of pure cotton, pure polyester, or polycotton blends with more than 50 per cent cotton), and a further 45 per cent is potentially recyclable once advanced textile recycling technologies are commercialised. An opportunity to create value is clearly being missed.

Landfilling of textile waste is problematic because an article of clothing could take more than 200 years to decompose, depending on the fibres used and the various treatments and finishes used on the fabric. Furthermore, while this article of clothing is decomposing, it generates greenhouse gases and can leach toxic chemicals and dyes into the soil and groundwater. Landfilling of textile waste is not a long-term solution, and if materials can be diverted and recycled, landfilling volumes could be reduced, encouraging longer material use and lowering the need for virgin materials.

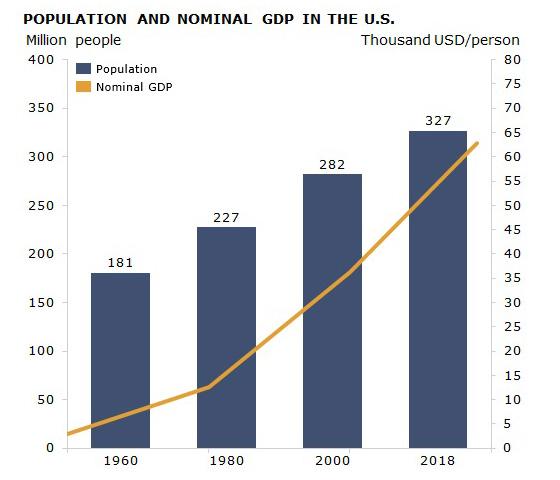

Take a moment though, and consider just how suddenly and quickly the generation of vast amounts of textile waste took place over the decades. There was a clear turning point in 1980 that steered the trend towards its upward trajectory. This point coincides with the sharp increase in GDP at about the same time (see Figure 3). This, paired with the fact that fast fashion became mainstream by the 1990s, meant that the average US household increased its overall consumption, including that of textiles, and inevitably, generated more and more textile waste. Will this trend continue in the future?

The Issue Ahead

According to the US Census Bureau, the country’s population is expected to increase by an average of 1.8 million people per year until 2060, and at this rate, it will cross the 400 million mark by 2058. This trend is markedly different from other developed countries in the world, particularly in Europe, whose populations are expected to either barely increase or shrink in the coming decades. So, unless the consumption habits of consumers in the US significantly change in the next few decades, the market for textiles will increase, and inevitably, more textile waste will also be generated. Alternatives to landfilling of textile waste thus need to be urgently found and implemented on a large scale. Luckily, there are some parallels one can draw to how another sector has been able to do exactly that some 50 or 60 years ago.

Lessons from Paper Recycling

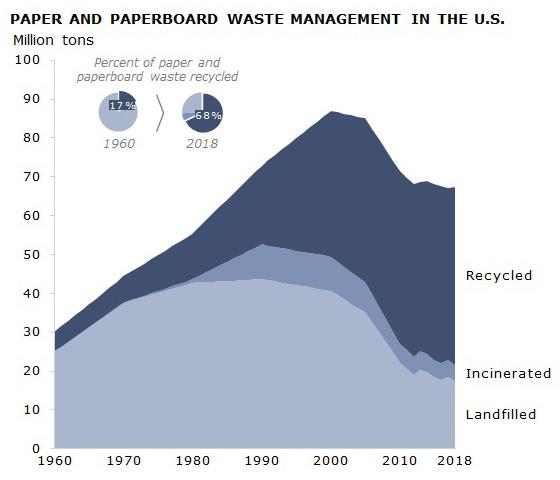

In the 1960s and 1970s, more than 85 per cent of generated paper and paperboard waste in the US ended up in landfills (see Figure 4). In fact, landfilling was the most popular form of waste disposal in the country after World War II. However, when disposable packaging and plastics became mainstream, landfills started to overflow and run out of space. That, combined with the growing environmental movement, saw the first real changes in the industry. By the early 1970s, the first kerbside recycling bin for paper, “The Tree Saver” was used, and by the late 1980s, the first statewide universal mandatory recycling law was enacted. Lawmakers went even further in the early 1990s, passing the first-ever statewide ban on landfilling of recyclable materials and by 1995, this included tires, aluminium containers, corrugated paper, foam polystyrene, plastic containers, and newspapers, as well as yard waste.

Regulations and legislation did certainly push innovation, however, funding and financial support for these initiatives was crucial. In the mid-1970s, for example, Massachusetts secured the first-ever EPA recycling grant to implement a weekly multi-material curbside collection program in two cities and use the first-ever residential recycling truck (Northeast Recycling Council, 2019). Without this financial support that proved such a system would be possible, and without further advancements in recycling technologies, we may still have to sort and transport recyclable materials to central recycling hubs ourselves.

Opportunities for Textile Recycling

There is a strong case to be made for the US to step up and establish itself as a front runner in the new circular economy for textiles. While there are already some regulations and legislations being passed to address this topic, such as California’s new Responsible Textile Recovery Act of 2023 that will require an extended producer responsibility (EPR) program for recycling textiles in the state as well as New York’s proposal for an EPR system, country-wise infrastructure for handling textile waste still seems to be missing. At present, the small fraction of textile waste that is being recycled in the US is performed mechanically via cutting, tearing, and shredding, which shortens the textile fibre length (an essential property needed for strong, high-quality spun yarns) with each recycling loop. While mechanical recycling of textile waste back into new textiles is commercially available, virgin fibres always need to be blended with recycled fibres to produce strong yarns. That being said, innovation is taking place—“soft” mechanical textile recycling, for example, can preserve much of the textile fibre length and achieve length reductions of only 10 to 15 per cent.

There are also more advanced textile recycling methods on the horizon, particularly those using chemical pathways. This innovation is taking place on a global scale, including in the US. Ambercycle, a California-based textile recycling startup, uses a molecular regeneration process with enzymes to break down textile waste into its constituent molecules. Regenerated polyester is then extracted from its process, further purified, and reconstituted into virgin-grade cycora® pellets. Another US-based start-up called Circ, headquartered in Danville, VA, uses a slightly different approach called hydrothermal processing. In this process, water, pressure, and responsible chemistry is used to separate polycotton textile waste into a cotton fraction that can replace dissolving wood pulp in the manufacture of man-made cellulosic fibres such as viscose and lyocell and purified terephthalic acid (PTA), which can be used to make polyester fibres. And then there is Evrnu, a start-up based in Seattle, WA, that has developed Nucycl® technology capable of converting cotton-rich textile waste directly into Nucycl® lyocell fibre.

This brings us back to the remaining components urgently needed for change to materialise—grants, funding, and other investment schemes are critical to jumpstart the industry and allow innovative approaches to textile waste management to be realised. To help speed up time-to-market, close partnerships and collaborations between all textile value chain players and waste and recycling industries will also be required.

With these concluding thoughts, we asked Karla Magruder, President at Accelerating Circularity, what her and her organisation’s views are on the main opportunities for textile recycling within the US. Her response was:

We all like to think about the exciting new recycling technologies. However, it is essential that we work on the sorting, aggregating, and preprocessing of feedstocks for the recycling process. The US has approximately 12 million tons of textiles going to landfill and incineration annually. These materials have the potential to be our biggest resource and opportunity for transitioning to a circular textile-to-textile system. The materials need to be diverted to collectors, sorted by fibre and potentially colour and fabric construction and then preprocessed into recycling feedstocks. Without these feedstocks, the recyclers will not have the necessary inputs for making recycled fibre.

This article was originally published in the December 2023 issue of The Waste Advantage Magazine.

Bioindustry Management Consulting

Our service offerings, from corporate strategy to process design and from market insights to operational efficiency backed up by an understanding of best practices, detailed in-house databases, and analysis led by experts in the field, ensure your outstanding performance. We want to be your trusted partner.