When lack threatens

A balance between decarbonisation and the security of wood supply

The ongoing green-energy transition involves shifting towards an ecologically sustainable economy as well as growth that is not based on the overconsumption of natural resources and fossil fuels. Although the background of the transition is therefore a need to mitigate both climate change and the unsustainable consumption of resources, even more momentum has been given by efforts to break away from energy imported from Russia. When looking for low-carbon solutions, all eyes have increasingly focused on raw wood material and bioeconomy. At the same time, however, the latest research results show that the carbon sinks provided by our forests have collapsed, endangering the achievement of national carbon neutrality goals. As a result, the use of forests will probably be more regulated in the future, which will mean that logging will hardly increase. Along with these prospects, the flow of imported wood from Russia has also stopped for a very long time. We are therefore on the verge of a difficult equation where on one hand, both the need for bio raw material and its potential uses are increasing, and on the other hand, its availability is decreasing while the important role of forests in the carbon balance must be taken care of. In this article, I set out to discover from the experts what kind of opportunities and challenges we have at hand.

A sudden change on the market

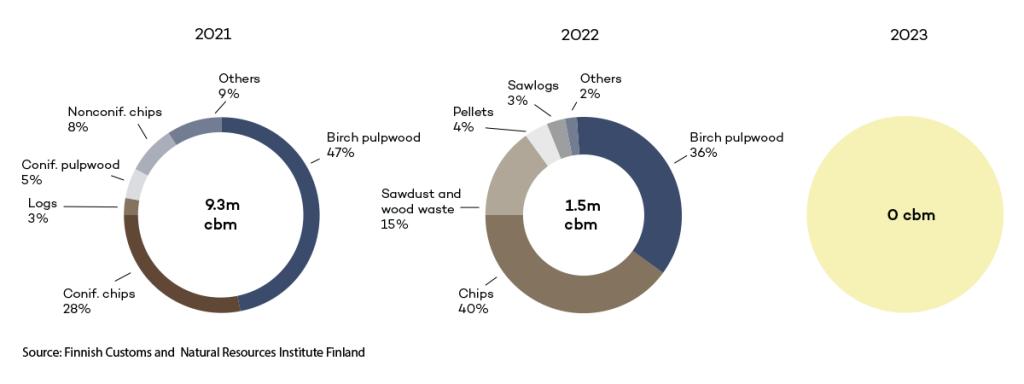

If we look at Finland's imports of raw wood material from Russia against the backdrop of the Russian war against Ukraine, we see a striking change. While imports in 2021 still amounted to 9.3 million cubic metres, they shrank to 1.5 million cubic metres in 2022 and came to a complete standstill in 2023. "Imports of raw wood material from Russia accounted for 10% of all raw wood material used in the Finnish forest industry in 2021," explains Timo Tolonen, Trade Policy Specialist at Finnish Forest Industries. "Among these, the most important wood grades were birch pulpwood and coniferous chips, which accounted for 75% of total imports. Their shortage is a challenge for the Finnish forestry and energy industries." Currently, this shortage is compensated primarily from domestic sources and commercial thinning and, in addition, through purchases from the Baltic region, such as Latvia and Estonia, as well as Sweden and Germany, Tolonen says. "But since there is fierce competition for the raw material, especially in the Baltic countries, this leads to sharply rising prices."

Although it is possible to import eucalyptus species from remote regions, Tolonen adds, the problem is the transport distance and the high associated costs. In some domestic factories, therefore, attempts are being made to replace birch pulp with coniferous wood, as far as the processes allow.

Challenges are still to come

However, the real challenges of the wood shortage will not become apparent until the end of 2023. At the same time, the European Climate Law includes provisions to allow the EU to become climate net neutral by 2050. To achieve this objective, both natural ecosystems and industrial activities should contribute to removing several hundred million tonnes of CO2 per year from the atmosphere. To support the integration of carbon removals into the EU climate policies, the EU has proposed a regulation of the carbon- removal certification. Malgosia Rybak, Climate Change & Energy Director at Cepi (Confederation of European Paper Industries), coordinates the pulp and paper industry’s position on the initiative that will develop the necessary rules to monitor, report and verify the authenticity of these removals. The aim is to expand biogenic carbon removals and encourage the use of innovative solutions to capture, recycle and store CO2 by farmers, foresters and industries.

Discussions on a carbon removal certificates have only just started and nothing is set in stone yet. According to Rybak, the establishment of a certification system for forest removals must be accompanied by a thorough impact assessment detailing the potential impact on raw materials availability and, consequently, the effects on the development of the EU forest-based circular bioeconomy. Cepi has proposed clarifications for the current proposal, for example, regarding the storage effect beyond the forest cycle. “As certificates could be attached to products storing carbon, their ownership should be given to the actor enabling the storage”, Rybak proposes. “This would be a way to acknowledge the benefit of prolonging the storage effect beyond the forest cycle and thus maximising the climate benefit”. The approach is based on the thinking that mature forests are more prone to decay and disturbances that may cause the carbon to be released again. It is also known that the carbon sequestration capacity of a growing stock decreases over time.

Changes in forest-management systems could be a part of the solution, as studies show that EU forests could store more carbon through sustainable forest management. “If we get the carbon-removal certification right, forest management may become a revenue stream per se, in addition to products certified for their carbon storage capacity”, says Rybak.

However, these changes may not be sufficient to balance the demand of wood and carbon sinks. It is clear that in addition to radical GHG emission cuts the level of carbon removals must be expanded, in order to reach the Paris Agreement goals. Rybak shares the view that increasing the forest area in Europe would be a win-win solution, enabling the highest potential for enhancing removals and securing wood availability in the long term.